KANSAS CITY, Kan. (BP) — Many of the top films of 2014 did their best to promote secular significance while avoiding a spiritual component found in the greatest films of years past.

Successes including “It’s a Wonderful Life,” “Dead Man Walking,” “Schindler’s List,” “Places in the Heart,” and “Tender Mercies” are works of art, both nurturing and entertaining. There were some good films this year, but no enduring classics.

One film comes close.

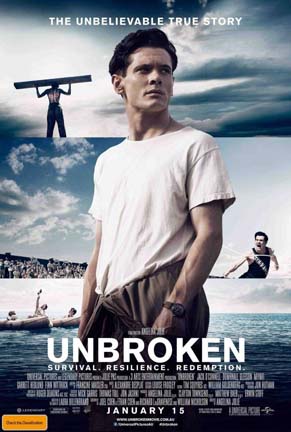

“Unbroken,” opening Christmas Day, details the early life of Louis Zamperini, an Olympic runner who was taken as a prisoner of war by Japanese forces during World War II after being stranded at sea for 47 days. Leaning on his faith, the POW was able to endure and eventually forgive the evil thrust upon him. Alas, this healing process and ability to forgive is only given in a couple of lines at the very end of the production.

“After years of severe post-traumatic stress, Louis made good on his promise to serve God, a decision he credited with saving his life.”

“Motivated by his faith, Louis came to see that the way forward was not revenge, but forgiveness.”

One leaves the theater suspecting the filmmakers missed the real story.

Please understand, Unbroken is a solid film, well acted, moving and instructive. Director Angelina Jolie bravely depicted Zamperini’s torment at the hands of the Japanese, despite the politically correct climate in which we live. The fierceness of Zamperini’s captors had to be depicted in order to reveal the man’s indomitable spirit and the grandness of his absolution. Jolie will catch some flak for the depiction, but it was a brave and honest decision.

It’s a good movie; but why isn’t it a great movie?

The answer lies in those two closing lines. We are told that Zamperini came to forgive his tormentors, including the camp commander known as the Bird, who was particularly barbaric. Reading those lines, I thought, there’s your story! The great majority of the 137-minute film includes seemingly endless scenes reflecting Zamperini’s suffering first at sea, and then in a POW camp.

Zamperini’s conversion and healing process are given virtually no screen time, but comprise the true story that needs to be told. Salvation and healing are Zamperini’s legacy, showing how a soul can find healing and peace.

How many films have we seen depicting soldiers enduring POW camps, while movies of survivors learning to forgive the horrific deeds done to them are few? If Zamperini can forgive those who bullied and beat him nearly to death, can we not forgive those who have mistreated us in more limited ways? So, show us the example, Hollywood!

I was privileged to speak with Luke Zamperini, Louis’ son. While he understood my frustration, he told me how his dad felt about the film. Louis died at the age of 97, but had been able to see a rough cut of the production, on Ms. Jolie’s laptop, no less.

— “My dad’s story was so immense I can’t imagine getting it into a single film,” Luke began.

— “We’re talking sequel?” I ask.

The son laughs. “There should be. The film is the way my dad would like it to be. Here’s why. He didn’t want it to be a film that just appealed to Christians. In his work as an evangelist, he was very subtle. He didn’t want to put the Gospel right in front of your face. His style was more to get you interested and have your curiosity get the best of you and to find out for yourself.

“I personally think this film accomplishes that. When you see those few lines you’re talking about shown over him running in an Olympics marathon in Japan [at age 80], with this joyous expression on his face, that will cause curiosity. That shot and those lines will get people to start thinking.”

Luke makes a good point. The symbolism of his father running with that smile on his face may indeed get people to think about spiritual matters.

“When do you think he came to terms of forgiveness?” I ask Luke.

“With his post-traumatic stress, life was really going down the tubes for him,” Luke responds. It was his mom who suggested he attend a local Billy Graham crusade. So he found himself in that tent meeting in 1949, Billy Graham’s first crusade in Los Angeles.

“[My father] remembered his promise to God made when near death at sea, that if He got him out of this, he would serve Him. So he went backstage to the prayer area and found a young counselor who led him in the sinner’s prayer. He told me that he realized at that moment he was done getting drunk, done fighting, that he’d forgiven his prison guards, including the Bird.

“A year later, instead of going back to Japan for revenge, he went there to preach the Gospel and to preach forgiveness. It was important to him to look his former tormenters in the eye and shake their hand and show that he had forgiven them.”

That picture of forgiveness is the great movie, yet unmade. Such a film would address the question, ‘How do we forgive those who trespass against us?’

In the filmmaker’s defense, there is nothing more difficult to bring to the screen than a depiction of spiritual healing and forgiveness. Faith is not seen by eyes. But there have been films more successful with addressing the question of how one comes to forgive monsters. Though I think Unbroken is worth viewing, I’ll leave you with two other films that are more open with how we can forgive others.

The telefilm “Amish Grace” is the true story about the aftermath of the 2006 schoolhouse shooting in the Amish community of Nickel Mines, Penn. The title of the book from which it is drawn, “Amish Grace: How Forgiveness Transcended Tragedy,” best summarizes the production’s theme.

Amish Grace is not a defense of a religious sect, but rather a penetrating examination of the concept of true forgiveness. The film may commit a few production misdemeanors, but it deals with spiritual truths and provides a positive answer to a nagging question.

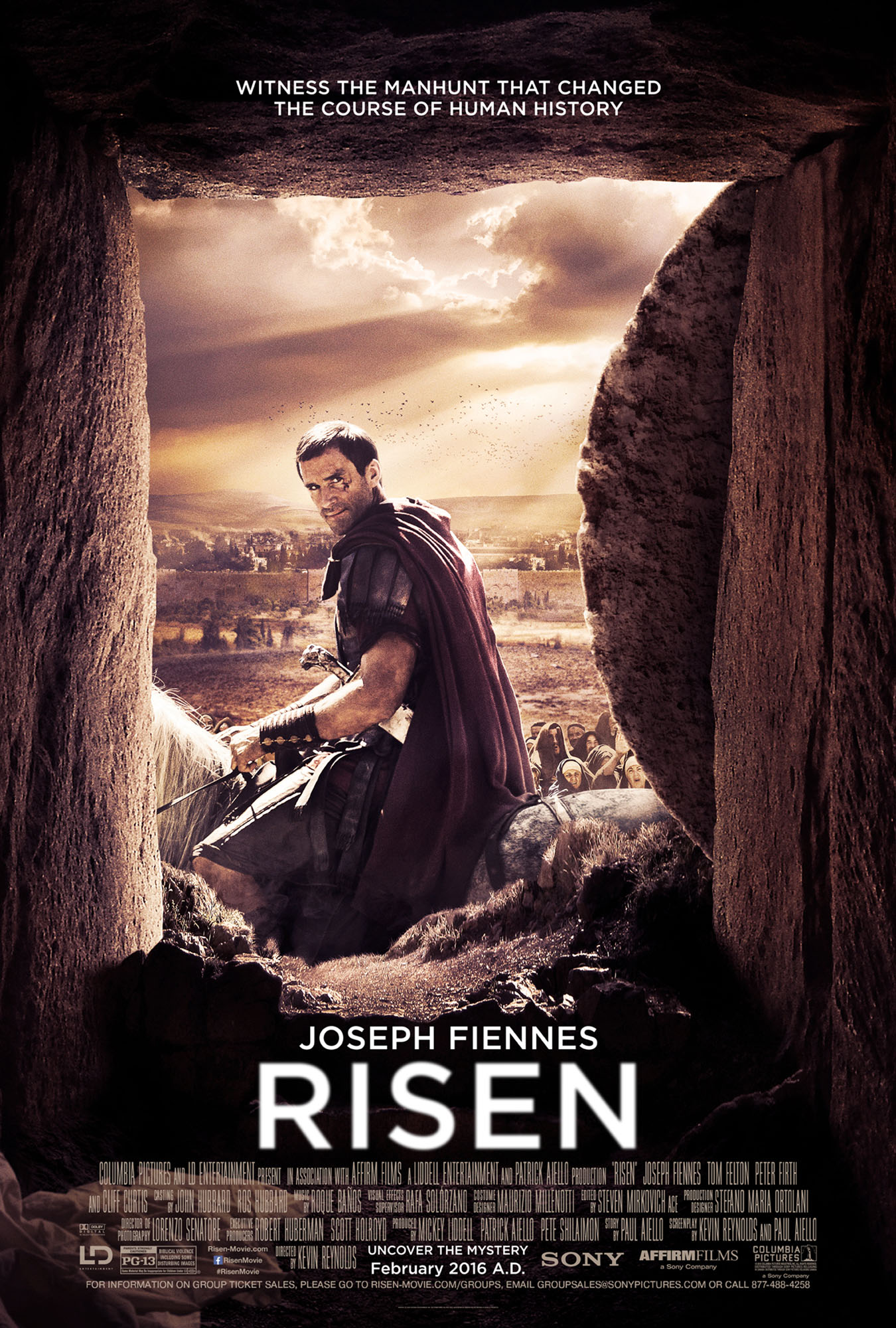

“The Scarlet and the Black” was a made-for-TV true story of a priest (Gregory Peck) who harbored allied POW escapees, and the Nazi official (Christopher Plummer) who tried to catch him. The film is long, 155 minutes, but the message contained should not be missed. A true example of Jesus’ compassion will help remind each of us to love our enemies.

One of the greatest mysteries of the Christian walk is this ability to forgive those who wrong us. After trying vainly to forgive others on my own, I have learned that hurts and a broken spirit can only be healed by the great physician Himself.

There’s your story.