RICHMOND, Va. (BP)–A dedicated American surgeon, beloved by nearly all who knew him, died 50 years ago — alone, in a cold jail cell far from home.

He was arrested in China on false charges based on planted evidence. He was beaten, ridiculed, jabbed with bamboo sticks by prison guards. Driven to distraction by brutal interrogations, he was despondent to the point of insanity in his final days, according to witnesses jailed with him.

But few believed the official story that the 43-year-old doctor had committed suicide after he was found hanging from a beam in his cell the morning of Feb. 10, 1951. A colleague allowed to view his body saw little evidence of a hanging — but plenty of marks of physical abuse.

He was quickly buried by a few friends under the close watch of an armed escort; no religious service was allowed. His remains were not returned to the United States until 1985.

What an injustice, many said at the time — and in the decades since. What a tragedy. What a waste.

Injustice, yes. Waste? Far from it.

Southern Baptist missionary Bill Wallace may have suffered keenly in his last weeks on earth, but he had long been prepared for it.

“Go on back and take care of the hospital,” he told co-workers when he was first arrested. “I am ready to give my life if necessary.”

Wallace was not the only foreign missionary martyred in China during the tumultuous years of a Japanese invasion, civil war and the beginnings of communist rule — which ended the missionary era. But his life story became as familiar to Southern Baptists of several generations as that of Lottie Moon, the missionary heroine who died serving China several decades before Wallace arrived.

Born in Knoxville, Tenn., in 1908, Wallace was the son of a doctor and as a boy tagged along with his father on patient rounds. At age 17 — while working on a car in the family garage — Wallace heard God’s call to medical missions. He answered yes, recorded the commitment on the back leaf of his New Testament, and never turned back.

After college, medical school and a surgical residency at Knoxville’s General Hospital, Wallace turned down a lucrative offer to become a partner with an outstanding surgeon. He was appointed in 1935 as a missionary to China by the Southern Baptist Foreign Mission Board — 10 years to the month after he made his garage commitment.

He went to Wuchow (now Wuzhou) in southern China, where missionaries at the Baptist-run Stout Memorial Hospital were desperately praying for a surgeon.

Wallace immediately gained a reputation as a kind man of few words (and a tone-deaf Chinese speaker when he did talk), a gifted surgeon, a tireless worker — and an absolutely committed servant of Christ, the gentle healer he emulated. A colleague once advised that anyone looking for Wallace should seek out the sickest patient in the hospital; Wallace would be there.

He worked through Japanese bombing raids as the stretchers of the wounded lined the halls — once finishing an operation after the hospital took a direct hit. After his first furlough back home, he returned in 1940 to a China on fire but refused to leave Wuchow as the invading Japanese closed in. To urgent appeals that he flee Wuchow, he responded, “I will stay as long as I am able to serve.”

Fellow missionary doctor Robert Beddoe wrote of one harrowing episode:

“At the time of the second severe bombing of the hospital, there was a desperately sick patient on the top floor. He could not possibly be moved without almost certain death. Wallace stayed by the bed, comforting and reassuring the patient. A bomb hit not more than 50 feet from the bed, tearing a gaping hole in the concrete roof. In the providence of God neither the patient nor Wallace was injured. One of the staff, who was four floors below at the time, told me he was lifted several inches by the concussion.”

Finally, in one of the great exploits of China missions history, Wallace evacuated the entire hospital in 1944, only a few days ahead of Japanese forces — transporting patients, staff and equipment by boat hundreds of miles upriver. There they tended the sick and suffering of the surrounding countryside until the advancing Japanese forced them to move again.

Wallace and his band of healers endured incredible hardships, but came back to Wuchow in 1945 when the tide of war turned. His description of their return in a letter home to his sister was characteristically brief:

“Dear Sis: Wuchow. Love, Bill”

Wallace repaired the badly damaged Stout hospital and got back to work. He nearly died from typhoid fever in 1948. After recovering, he kept right on working in Wuchow after the communist defeat of the Nationalist Chinese in 1949 — earning even the grudging respect of communist soldiers as he treated their wounds.

But missionaries were no longer welcome in China, and the start of the Korean War in 1950 sparked an intense anti-American propaganda campaign. Wallace’s arrest came in December of that year after local authorities “found” a gun under his mattress during a search and accused him of being a spy. He died in jail less than two months later.

But it wasn’t his lonely death that defined Wallace’s heroism. It was his love-filled life.

Yes, Bill Wallace “was a martyr,” acknowledged the late Everley Hayes, the missionary nurse who worked with him in his last years and identified his body.

“Many think of martyrs as those long-faced people. But I knew a Dr. Wallace who was very much interested in everything around him. He was a martyr not because he died in service but because he so identified with the Chinese people that they considered him one of them. And they loved him.”

After Wallace’s arrest, a commissar summoned many Wuchow citizens to a public meeting and demanded that they step forward to denounce the missionary. Not a single person did. The only charge they could make stick, reflected a Roman Catholic missionary who knew Wallace, was that “he went about doing good.”

In an unheroic time, many Americans are looking back with new admiration to what newsman Tom Brokaw has dubbed “the greatest generation”: the men and women who endured the Depression, then landed under fire on foreign shores to help defeat the Nazis and their allies.

The ones who survived came home to build lives, families, a nation. Reticent about reliving their hour of terror and courage when so many died, most of these living veterans — when pressed — usually say they “did what we had to do” and leave it at that.

Alongside these quiet heroes of war, consider quiet Bill Wallace of Tennessee, a man of peace who gave his last full measure of devotion to heal bodies and souls in an isolated corner of China. He didn’t have to do what he did. He did it because he wanted to. Chinese friends in Wuchow understood that when they risked punishment to put up a monument on his unmarked grave with these words from the apostle Paul: “For to me to live is Christ.”

The Chinese had heard sermons before, but “in Bill Wallace they began to see one, and that made the difference,” missions historian Jesse Fletcher wrote.

In an age of hype, character speaks infinitely louder than words. Duty, commitment, compassion, humility, courage, obedience to God: If you’re looking for ways to share those qualities with your children, give them a copy of Fletcher’s classic biography, “Bill Wallace of China” (Broadman & Holman). Then pray for the Bill Wallaces God is raising up in this generation.

Your son or daughter may be one of them.

–30–

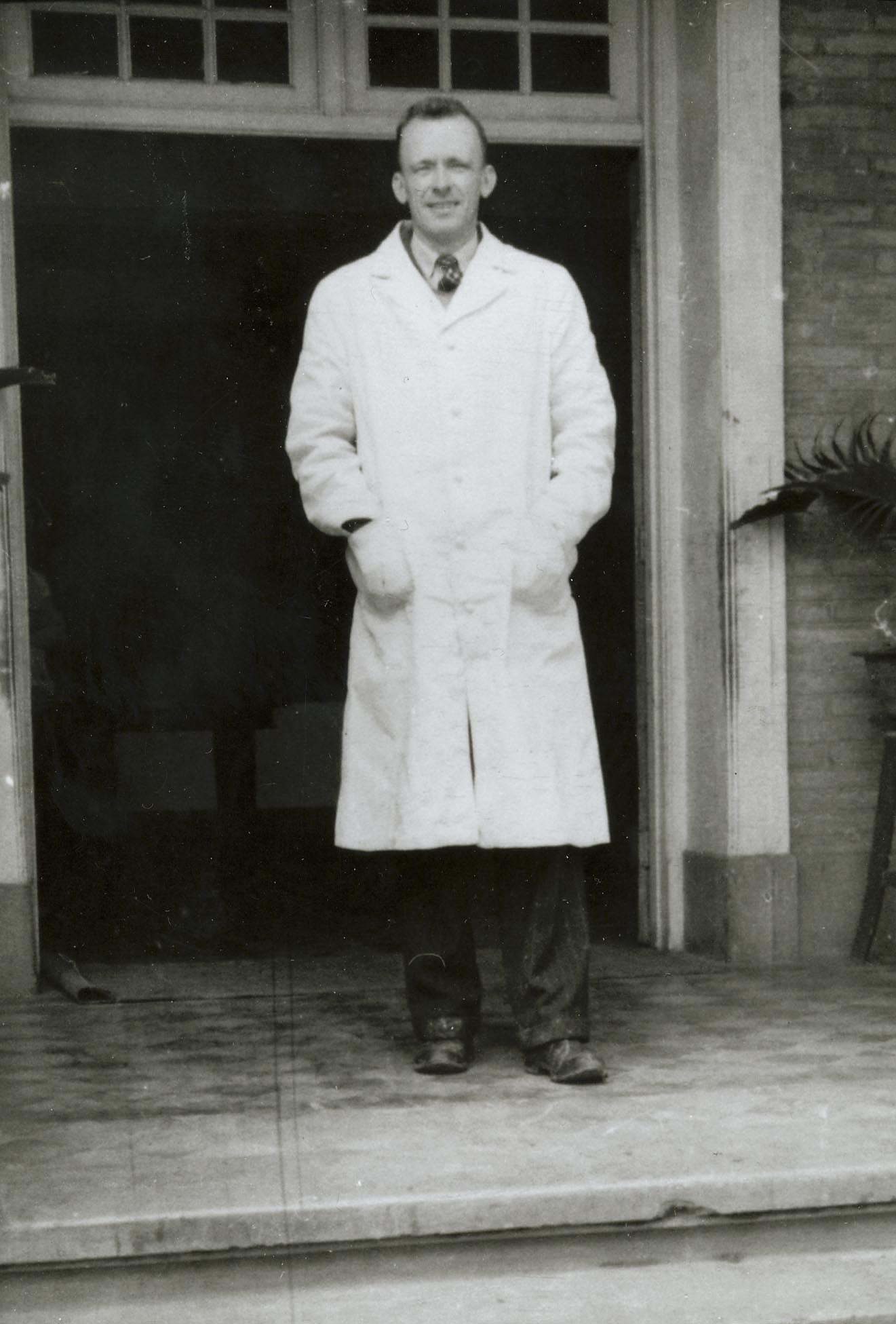

(BP) photos posted in the BP Photo Library at https://www.bpnews.net. Photo titles: GENTLE GIANT and GRACE UNDER FIRE.

— Has the story of Bill Wallace affected your life over the years? In what ways? Share your reflections on Wallace’s legacy at www.imb.org/forum.

— To order “Bill Wallace of China” by Jesse Fletcher, call LifeWay Stores Customer Service at 1-800-448-8032 or search for it at www.lifewaystores.com/lwstore/search.asp.