NASHVILLE (BP) — The Civil War was fought 150 years ago, but without a small band of abolitionists driven by their Christian faith, the war might never have happened.

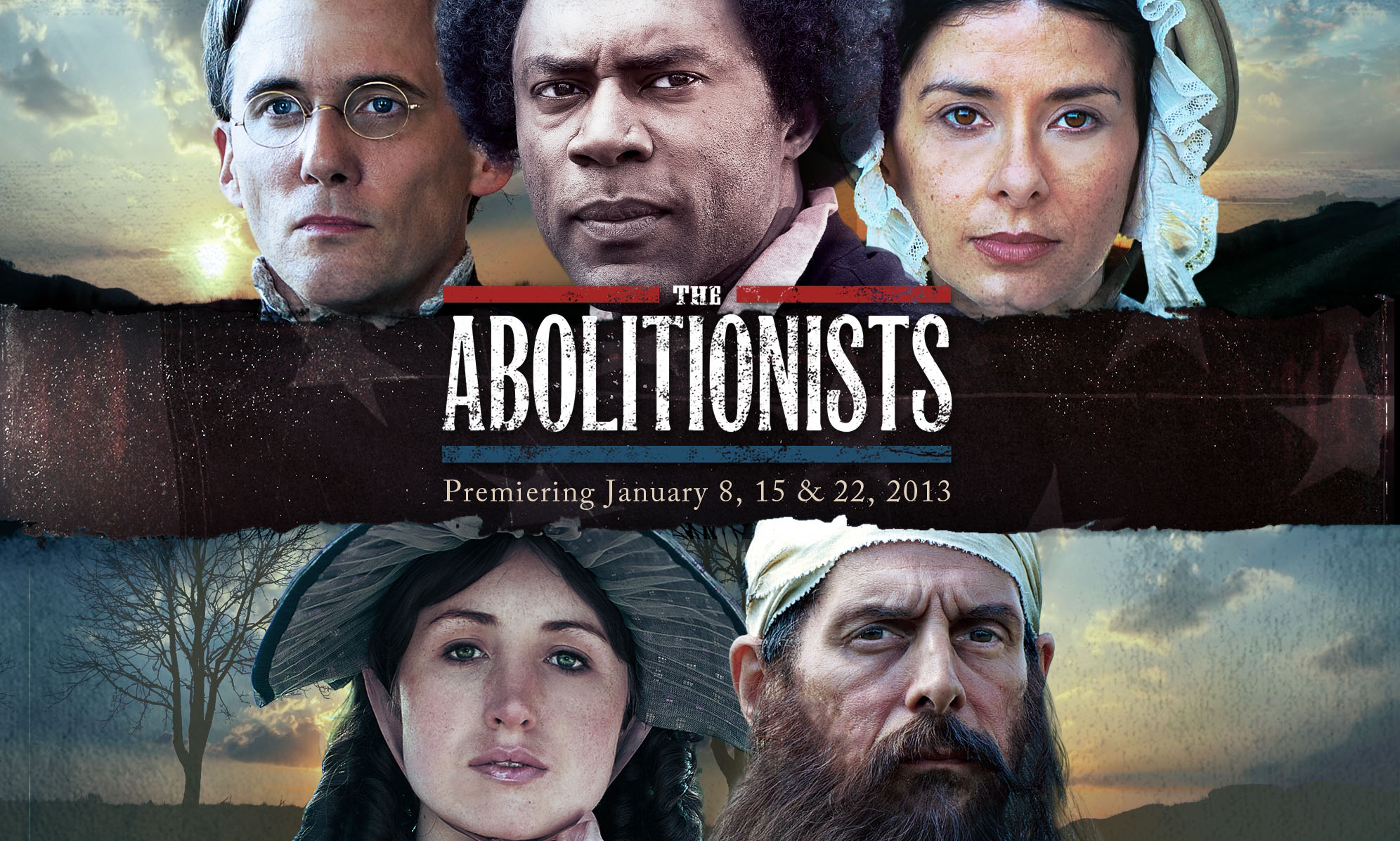

That’s the conclusion of a three-part PBS docudrama that will premier Tuesday (Jan. 8). It doesn’t shy away from recounting the religious beliefs of abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison, John Brown, Frederick Douglass, Angelina Grimke and Harriet Beacher Stowe. They believed slavery was a sin, and they set out to cause its demise. In turn, they helped change a nation.

Parts two and three of the series, known simply as “The Abolitionists,” will air Jan. 15 and 22. It is the latest installment in PBS’ popular “American Experience” series.

Each episode is one hour long and is part documentary, part re-enactment. It is rated TV-PG, with some violence and language in the first two episodes.

The series tells how Grimke, the product of a slave-owning family in South Carolina, came to see slavery as unbiblical.

“She believed slavery was a sin and that God would punish people who had slaves,” historian Carol Berkin says in the series.

The docudrama recounts how Garrison, in his 20s, began publishing an anti-slavery paper, convinced that God was on his side.

“William Lloyd Garrison’s religious background was not just a background, it was at the core of who he was,” historian James Brewer Stewart says in the series.

Baptist Press spoke about the abolitionists with Daniel W. Stowell, director and editor of The Papers of Abraham Lincoln (Springfield, Ill.), a project whose goal is to digitize Lincoln’s writings. (Stowell grew up Southern Baptist and now attends a General Association of Regular Baptist church in Illinois.)

Following is a transcript of the interview, edited for clarity:

BAPTIST PRESS: What role did the abolitionists play in ending slavery in the United States?

DANIEL W. STOWELL: They played a broad role in mobilizing public opinion. Lincoln famously said “whoever controls public opinion controls the government.” They nudged Lincoln; they nudged the North in general toward a view of how slavery was corrupting the nation. They played an important role in moving the public in a direction that Lincoln could ultimately issue an Emancipation Proclamation as a war measure. There’s still a lot of racism in the North during the Civil War. Lincoln is never what I would classify as an abolitionist; he’s anti-slavery. It remains a very open question how much sympathy he had for enslaved African Americans vs. the corruption that slavery wrought in the nation at large.

BP: And there were times that the abolitionists themselves thought that Lincoln was on the wrong side of the issue and that he was working against them.

STOWELL: Absolutely. The famous book on this is Lerone Bennett’s “Forced into Glory,” where he basically argues that Lincoln was forced into issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, and that each of his actions against slavery were forced by abolitionists and radical Republicans. I think that’s too simplistic. The kernel of truth that lies in it, however, is that Lincoln was not a Garrisonian or a John Brown type of abolitionist, where the abolition of slavery is the only thing that matters. I believe Lincoln considered slavery to be a corrupting influence — it was bad obviously for the slave, but it was also bad for the white Southerner, it was bad for the white Northerner, it was bad for the politics of the nation.

BP: One historian in the documentary says that without the abolitionists, the Civil War would not have happened. Do you agree with that?

STOWELL: I would agree with it in the sense that Southern perceptions of Northern society were such that the election of a Republican president [Lincoln], by itself — with no actions by that president — led to several states seceding, before he is even inaugurated. Abolitionists frightened Southerners to the point that the mere election of a Republican president was cause for secession. On the other hand, one can be anti-slavery and anti-African American. It raises the question then of whether slavery, as distinct from racism, caused the Civil War, and I would argue that it did — slavery caused the Civil War.

BP: The abolitionists, then, dramatically impacted the Southerners’ view of the North?

STOWELL: Absolutely, although Lincoln and other Republicans tried very hard to distinguish themselves in the public mind from the abolitionists. But Southerners would have none of it. They referred to Lincoln as a black Republican.

BP: We view the abolitionists as being successful, as very optimistic, as seeing a country where slavery someday will not exist. But weren’t there many times when the abolitionists were pessimistic?

STOWELL: The hopefulness of abolitionists waxed and waned, often waning after poor performances in political contests. At times they had cause to despair. One of the clear examples of despair would be after the Dred Scott decision, of course. They were appalled that the Supreme Court of the United States would make such a decision. They certainly were disheartened but did not give up.

BP: In watching this documentary, it seems that Christianity was a driving force behind many, if not most of the abolitionists. What role did faith play in the beliefs of the abolitionists on slavery?

STOWELL: The belief that African Americans are fellow human beings, and therefore deserving of God’s love and of love of their fellow man, certainly plays a critical role in the motivation of most abolitionists. Their beliefs often, if not always, had a religious motivation — do unto others as you would have them do unto you; love your neighbor as yourself. Of course, many of the same religious traditions are feeding into a very pro-slavery argument at the same time. Evangelical religion does not make all white Americans in the 19th century anti-slavery or abolitionists.

BP: Let’s mention some of the names in the documentary and examine their religious beliefs: William Lloyd Garrison, John Brown, Frederick Douglass, Angelina Grimke and Harriet Beacher Stowe.

STOWELL: Douglass’ religious views are a little murky to me. But certainly Brown, Garrison, Grimke and Stowe and many others who were allied with them come from a very strong sort of religious motivation. In Brown’s and Garrison’s case, they feel it is a religious mission, a meaning for their lives, to oppose slavery. It’s hard to quote from their writings and ignore [their faith].

BP: Yet despite the common thread of Christian faith among the abolitionists, they had different beliefs about how to end slavery, didn’t they? Some were pacifists; some were radical and wanted to start a war.

STOWELL: Right. Brown is willing to employ violence in that quest. Douglass teeters and is on the verge of joining with Brown, and ultimately does not. There are others who [also] see that as absolutely not the way to go, either from a non-violence perspective or from a perspective that [Brown’s approach] was foolhardy. [They felt] the way to effect change is through the political system, and we need to continue to educate our fellow citizens about the horrors of slavery and the moral obligations of all citizens.

BP: What can we learn from the abolitionists that perhaps we can apply today?

STOWELL: The parallels are often drawn to the hot-button issues of today. What it can tell us is that a small committed group can change public opinion over time, that there will be setbacks — as there were with the abolitionists — but that there will be victories as well.

–30–

Michael Foust is associate editor of Baptist Press. Get Baptist Press headlines and breaking news on Twitter (@BaptistPress), Facebook (Facebook.com/BaptistPress ) and in your email ( baptistpress.com/SubscribeBP.asp).