EDITOR’S NOTE: Feb. 9 is Racial Reconciliation Sunday on the Southern Baptist Convention calendar.

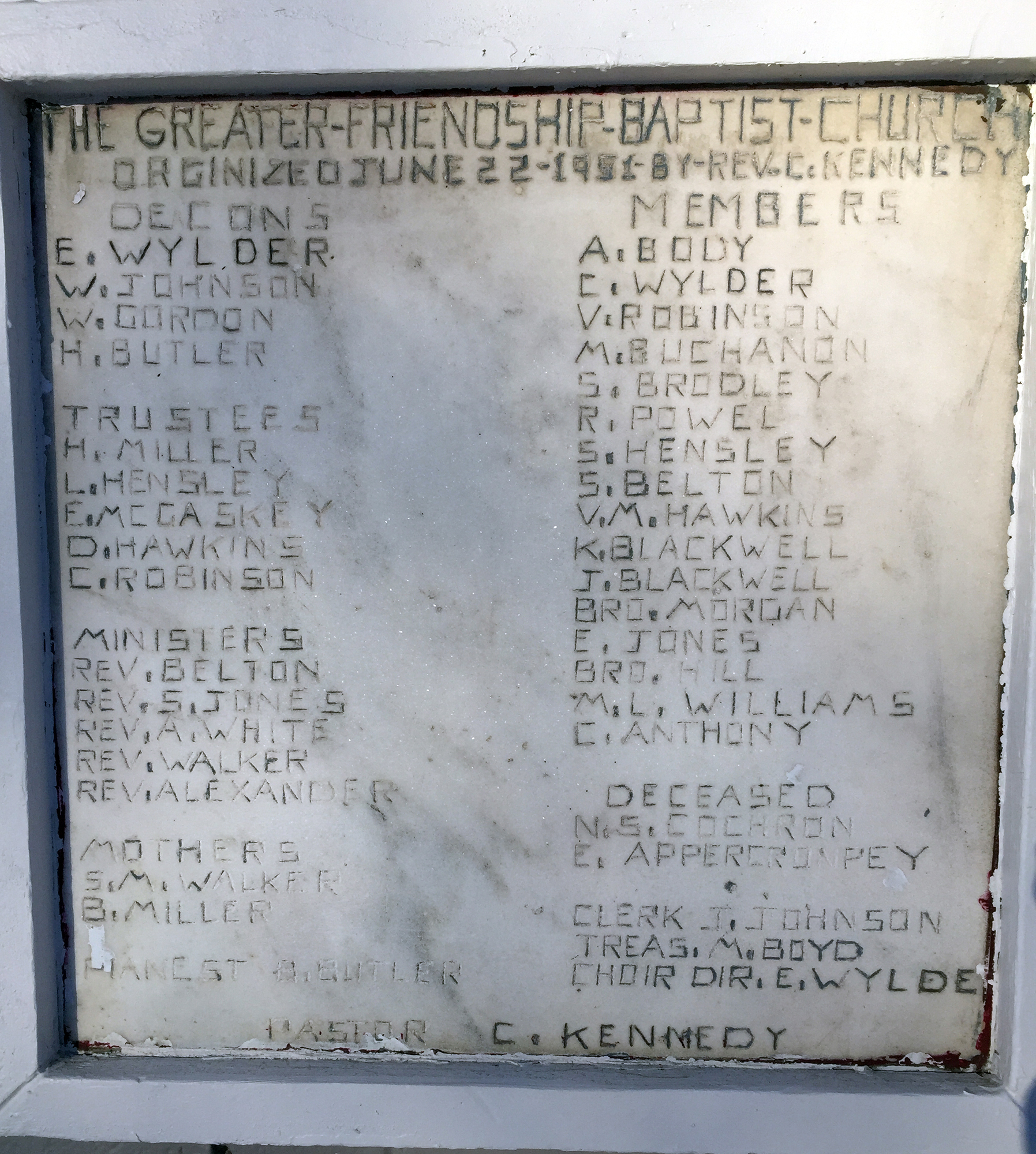

ANCHORAGE, Alaska (BP) — It’s significant that the National Register of Historic Places now honors Greater Friendship Baptist Church as the first church founded by blacks on Alaskan soil, its pastor Michael Bunton told Baptist Press Friday (Feb. 7).

But Bunton has a broader vision for the church distinguished as the first black Southern Baptist congregation — at least since the 19th century — when it was founded in 1951.

But Bunton has a broader vision for the church distinguished as the first black Southern Baptist congregation — at least since the 19th century — when it was founded in 1951.

“When I got here five years ago, I made it plain and clear that we don’t want to be known as the first African American church in Southern Baptists,” Bunton told BP. “We want to be the most successful multicultural church in Alaska, that’s our goal.”

Yet, the church saw fit to petition the federal government to be listed on the national register, an honor bestowed June 21, 2019.

“We wanted Alaska and the Southern Baptists to understand that we as African Americans are vital in the growth of Christianity in this state and in this nation. And we are a pillar in our community,” Bunton told BP. “The two or three major churches that are prominent were birthed from Greater Friendship.”

Greater Friendship birthed New Hope Baptist Church, a Southern Baptist congregation founded in 1960; and one of Greater Friendship’s former ministers, Frank Taylor, in 2000 became the senior pastor of Solid Rock Baptist Church, another black Southern Baptist congregation in Anchorage. Today, eight majority black congregations are members of the Alaska Baptist Resource Network (ABRN), executive director Randy Covington told BP. In addition to Greater Friendship, New Hope and Solid Rock, they are River in the Desert Community Church and Gilead Ministries in Anchorage; and St. John Baptist Church, New Birth Christian Church and Mt. Pleasant Baptist Church, all in Fairbanks.

Greater Friendship birthed New Hope Baptist Church, a Southern Baptist congregation founded in 1960; and one of Greater Friendship’s former ministers, Frank Taylor, in 2000 became the senior pastor of Solid Rock Baptist Church, another black Southern Baptist congregation in Anchorage. Today, eight majority black congregations are members of the Alaska Baptist Resource Network (ABRN), executive director Randy Covington told BP. In addition to Greater Friendship, New Hope and Solid Rock, they are River in the Desert Community Church and Gilead Ministries in Anchorage; and St. John Baptist Church, New Birth Christian Church and Mt. Pleasant Baptist Church, all in Fairbanks.

Greater Friendship has been active in Southern Baptist life.

The Southern Baptist Convention at its 1991 annual meeting in Atlanta recognized the church as the first black Southern Baptist congregation. The Kennedy Boyce Award, established by the Black Southern Baptist Denominational Servants Network to recognize black trailblazers, is named in part for Greater Friendship’s founding pastor Charles Kennedy. Leo Josey Sr., who pastored Greater Friendship from 1962-1969, was the first black elected to a statewide Southern Baptist post in 1966 when he became vice president of what was then the Alaska Baptist Convention.

The Kennedy Boyce award also recognizes Washington Boyce, the founding pastor of Community Baptist Church in Santa Rosa, Calif., formed Sept. 21, 1951 as the second black Southern Baptist congregation.

Greater Friendship was organized before the U.S. officially desegregated schools through the Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954 and before Alaska became a state in 1959. David Reamer, a historian who has documented Greater Friendship’s history and compiled the application that garnered the national historical register designation, said blacks have enjoyed greater opportunity in Alaska than in southern states hampered by Jim Crow, lynching and other ills.

But Bunton said the state still suffers racism, pointing to discrimination that he says stems in part from the small size of the black population that has left it difficult to gain a foothold in political decision making. The indigenous population, which according to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights includes 228 federally recognized tribes, also experiences discrimination, Bunton said.

But Bunton said the state still suffers racism, pointing to discrimination that he says stems in part from the small size of the black population that has left it difficult to gain a foothold in political decision making. The indigenous population, which according to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights includes 228 federally recognized tribes, also experiences discrimination, Bunton said.

“We are still battling the sense of discrimination here,” Bunton said, “but I think as pastors, the church has to stand up and begin to vocalize the prejudices against the Alaskan African American community as well as the minority.

“And the natives are very much discriminated against, more than we are, but it’s a challenge for us both to do what we can do without the benefit of having political power, without having the resources and the finances to fund our different goals,” Bunton told BP. “But we’re pressing forward and we’re going to change Alaska for the better.”

Blacks comprise only about 3.8 percent of Alaska’s 731,545 people, according to 2019 U.S. Census estimates. The state is also 65.3 percent white, 15.4 percent American Indian and Alaska Native, 6.6 percent Asian, 7.2 percent Hispanic or Latino, and 1.4 percent Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander.

Southern Baptists are working to reach the diverse landscape. Bunton sees challenges in reaching blacks, of whom he says less than 10 percent attend church services every Sunday. Covington sees additional challenges in reaching the native populations, which he says suffer disenfranchisement.

In addition to eight majority black congregations in the statewide ABRN, the 120-church network includes eight native churches and missions, and 10 Asian congregations.

Bunton is revamping his evangelism ministry and is trying to extend his global reach through social media.

“What we are really engaging in is how to evangelize more effectively, even in our community, our state as well as our nation and our world,” Bunton said. “Our vision and our mission statement is to train and disciple people to be followers of Jesus Christ through the Word of God, regardless of color, regardless of creed and ethnicity. So what we’re doing now is developing a plan.”

Located in what Bunton describes as one of the poorer ghettos in Anchorage, the church owns two lots, has a vision to purchase eight entire blocks and hopes to secure government grants to build medical and housing facilities to minister to the population suffering homelessness and substance addiction. In Bunton’s five-year tenure, he has grown the church from 18 members to nearly 170, he told BP.

“When I got here in November 2014, I think it might have been eight to 10 people I was preaching to. But now, even of last Sunday, we had at least 170 people, including children. So we’re just trying to win people over with the love of Jesus Christ, first and foremost, and not put a color shade on it. But we want to reach out to all ethnicities.”

With blacks comprising less than 4 percent of the population, Bunton pointed out, “if we limited ourselves to just African Americans, we would fail as a church.”