PHOENIX (BP) — When pastor Shaun Whitey asked First Indian Baptist Church in Phoenix to write down their tribal affiliation, people from nearly all of Arizona’s federally-recognized tribes were represented in the congregation that Sunday, 22 people groups in all, which Whitey described as typical.

The church reaches a broad cross-section of tribal groups in its aim to carry the Gospel to all the state’s reservations, Whitey said, yet faces an ongoing challenge of adequately preparing disciples who multiply other Christians.

The church reaches a broad cross-section of tribal groups in its aim to carry the Gospel to all the state’s reservations, Whitey said, yet faces an ongoing challenge of adequately preparing disciples who multiply other Christians.

“There are several reasons why Native people come to the city: work, school or other opportunities,” said Whitey, of Navajo/Seneca-Cayuga heritage. “But there’s still the draw for folks to go back home: family, emergency conditions. That makes it difficult to get things like discipleship started.

“For Native people, family is probably the greatest influence and highest value,” Whitey told SBC LIFE, the journal of the SBC Executive Committee. “Second would be the love for their people, their tribe.”

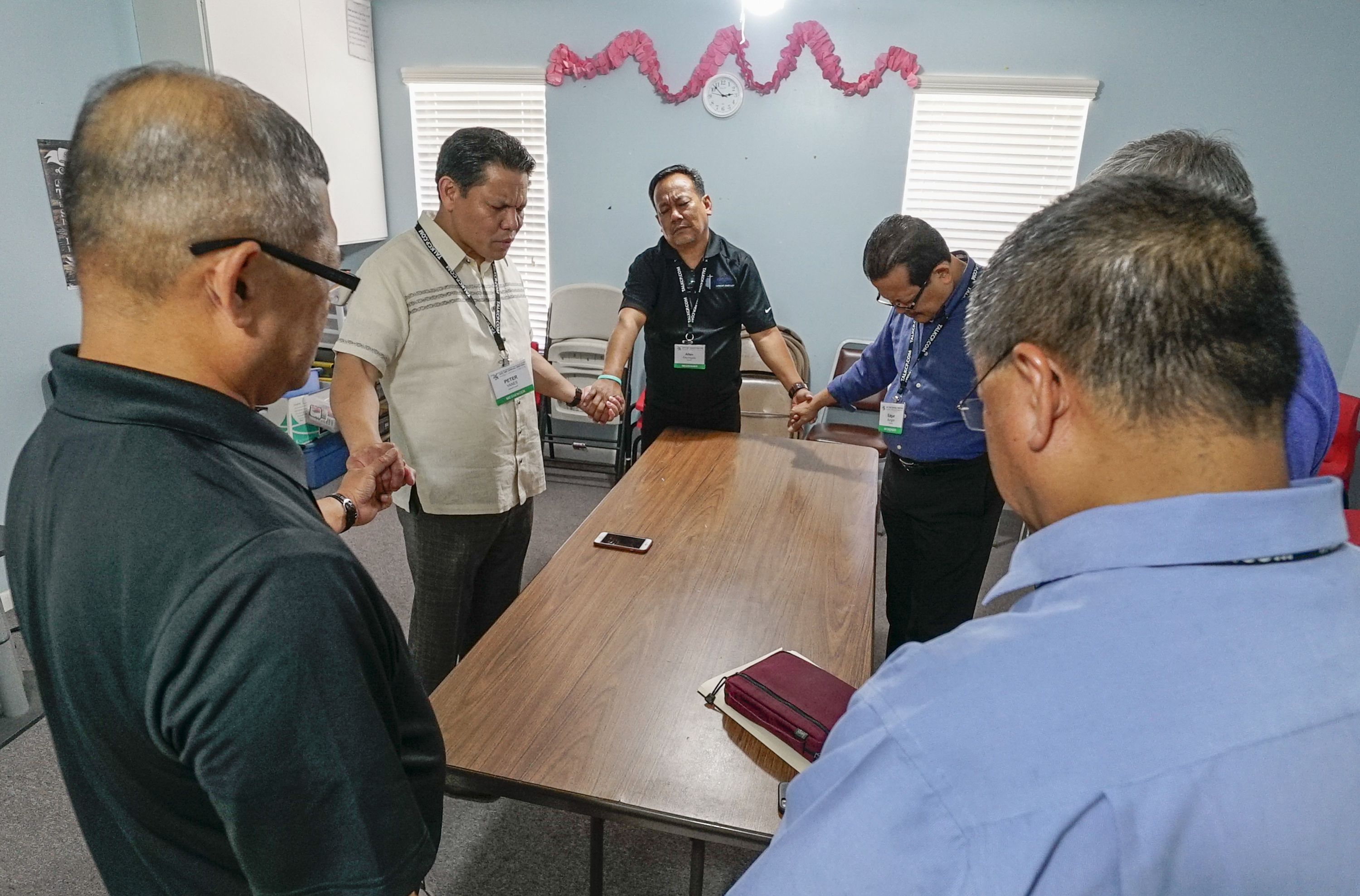

Evangelicals interested in ministering among Native Americans across North America participated in a two-day conference, “Dimensions to Native Ministry,” led by the Southern Baptist Fellowship of Native American Christians (FoNAC) and hosted by First Indian Baptist Church on the Saturday and Sunday prior the SBC annual meeting in Phoenix.

The purpose of the conference, FoNAC’s Executive Director Gary Hawkins said, was to “Discover people, places and partnerships; Develop networks, resources and ministry teams; and Deploy prayer warriors, volunteers and leaders.”

The purpose of the conference, FoNAC’s Executive Director Gary Hawkins said, was to “Discover people, places and partnerships; Develop networks, resources and ministry teams; and Deploy prayer warriors, volunteers and leaders.”

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2010 estimate, 2.4 percent of the population in metro Phoenix — or about 110,000 of the region’s 4.6 million people — is Native American. North Phoenix Baptist Church started First Indian in the 1960s as a mission to better reach them.

North Phoenix’s initiative was an early awareness of the need for Natives to reach Natives, Whitey said, a concept that in recent years has grown into a missional strategy.

“We realize we have many Native churches that are small and struggling, for many years depending on lots of help from the outside,” said Tommy Thomas, church planting catalyst for five associations in northern Arizona.

“Over time, these have become inundated with western, Anglo culture,” Thomas continued. “We want Native churches led by Native leaders. We want to respect the culture … to have sound, solid biblical doctrine, preaching and teaching by indigenous leaders.”

“Over time, these have become inundated with western, Anglo culture,” Thomas continued. “We want Native churches led by Native leaders. We want to respect the culture … to have sound, solid biblical doctrine, preaching and teaching by indigenous leaders.”

FoNAC independently came to the same strategy when it was started in 2008. Ministry among Native people in North America has changed over the last few years from “going to” to “working with,” Hawkins said.

“We saw the need for a new paradigm” of “equipping instead of just meeting needs, telling the Gospel story through the heart language and calling out versus sending in,” said Hawkins, a member of the Muscogee Creek Nation. “We encourage the support of non-Natives to partner with those utilizing this missional approach to ultimately establish healthy, reproducing indigenous churches.”

Whitey, as a Native American, and Josh Hodges, an Anglo, reflect the effectiveness of that missional strategy, Hawkins said. Whitey is mentoring Hodges, serving as a replanting pastor since last September of Indian Baptist Fellowship in Mesa, Ariz., which First Indian originally started in 1995. Hodges, in turn, is mentoring Troy Butler, a Navajo seen by Hodges as having the giftedness and calling of God to become a pastor.

Hodges is one of several Anglo pastors and three returning International Mission Board missionaries in Arizona with a similar story: Each recently came to the state inexplicably and individually called to Native ministry. They are now immersing themselves in the culture of the tribe or tribes in which they’re ministering.

“We’re so sparse with Native leadership that somebody’s got to come and spend time with these [Native] guys on their terms, and that’s what Josh and others are doing,” Whitey said.

“Josh is meeting with people in their homes, on their terms, on their reservations. Building a culture of trust takes time and consistency. This is one of the most challenging things to do in our fast-paced, results-based world.”

Time is an essential component to the spread of the Gospel among Natives, Whitey said. “Josh spends time with new believers in Christ by just going out there every week, and he is able to help them understand foundational truths of the Bible.”

He does so, Hodges said, by “trying to be their friends, to learn from them and not just tell them what we know. Our mission is to come alongside and equip and train and send people out, and not just do the work ourselves….

“The narrative of Christianity among Native people will only change when it comes through Native people,” Hodges said.

Foundational truth is another essential component of ministry to Natives, Whitey said, to counter the problem of a “Christianity-plus-Native-religion” syncretism, which is a divisive influence affecting many Native churches nationwide.

“All the churches I’ve been involved with to some degree have a tribal undercurrent that must be reconciled with the Gospel,” Whitey said. “There is always the tribal way and the Jesus way.”

Some cultural elements that might seem fascinating to a non-Native, such as eagle feathers and Native drums, have spiritual connotations that can confuse people, Whitey said.

“You just have to be very careful and ask, ‘What’s the meaning behind this?’ There are cultural elements that people can still be part of, but you must always discern the spiritual content,” he said.

An ongoing battle is the lasting effect of wounds caused by mistreatment of Native peoples in Native history. While the higher road is desired — to forgive — the lasting impact on Native people remains, so it is extremely difficult for them to forget, Whitey said.

All this Hodges and the other Anglos ministering to Natives in Arizona are learning. For First Indian Baptist in Phoenix, with Whitey as an electrical engineer and bivocational pastor, growing and nurturing disciples is a challenge in a place where people are continually in transition between reservation and city, as well as the church’s meeting place moving locations three times in the last 10 years.

“Relationships are key,” Whitey said. “You cannot speak into a Native person’s life without a relationship. The relationship cannot be forced and is best when sustained over time.”