If the Opening Ceremonies from Paris left a bitter taste in your mouth that affected your enjoyment of the Olympics, the remedy may just be reliving the athletic prowess – and courageous Christian determination – of Scottish runner Eric Liddell from the games 100 years prior.

It’s an iconic Olympic story that almost didn’t happen. Liddell was born in China to missionary parents, returning to Scotland to play rugby and get an education. He had a natural ability to sprint, and he soon began training for the 1924 Olympics, which, like in 2024, were hosted by Paris.

He began setting British records in some of the shorter races. He quickly became a favorite for the medal stand in Paris. But in the leadup to the games, he discovered the preliminary heats that would get him to the final races were scheduled for Sunday. Liddell’s Christian faith would not let him run on the Lord’s Day. Amid pressure from his fellow athletes, he bowed out of the race rather than, as he put it, run afoul of the fourth commandment to remember the Sabbath and keep it holy.

So he turned his attention to the longer races that didn’t have any heats on Sunday. Though he was best suited to short sprints, he still won bronze in the 200-meter race. The next day, his legs still aching from the previous race, he took home the gold medal in the 400-meter race. While other runners paced themselves at the start of the long race, Liddell would sprint the whole course. “I run the first 200 meters as hard as I can,” he told reporters. “Then for the second 200 meters, with God’s help, I run harder.”

Even after his Olympic career crossed the finish line, Liddell continued to “run the race.” In 1925, he returned to the mission field in China. He taught science and Bible at a boys’ school and was, unsurprisingly, an athletic coach. He remained in China even as the Japanese invaded in the lead up to World War II. In 1941, he sent his pregnant wife Florence and his two daughters to safety in Canada. They never saw each other again. Two years later, in 1943, Liddell and other foreigners were placed in an internment camp. Even there, Liddell embraced his mission from God and taught children math and science and organized athletic events inside the small camp.

Suffering from malnutrition and poor living conditions, Liddell collapsed and died in 1945 in the camp, succumbing to an inoperable brain tumor. According archives at the University of Edinburgh, his final words were, “It’s complete surrender.”

As compelling as his life is, if you know the name of a track star from a century ago, it’s almost certainly due the movie that tells his story, 1981’s “Chariots of Fire.”

It’s a fairly accurate retelling, weaving in the racing careers of Harold Abrahams, a fellow British runner facing his own personal struggles (namely his personal pride and the casual antisemitism his Jewish-ness prompts). It plays with a few facts for the sake of drama. For example, in the movie Liddell is surprised that the heats will take place on Sunday as he boards the ship to Paris, when in reality he knew months in advance and was able to shift toward the longer races.

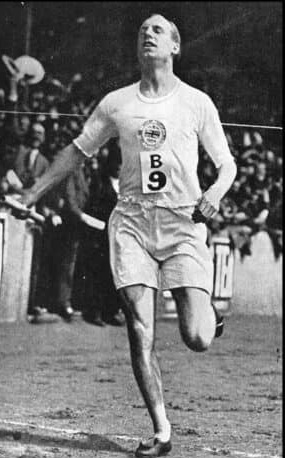

What it nails, however, is his Christian faith. Most movies with a faith element, even the best ones, often come across preachy, and their subject, too perfect. Perhaps because it also tells Abraham’s journey to Olympic greatness, “Chariots of Fire” somehow makes Liddell’s devotion and commitment to God seem a natural extension of who he is, rather than some character reading from a script. When he quotes Scripture, it’s not shoehorned in, and when he speaks of the mission field in China, it’s not treated as an oddity. Ian Charleson, who plays Liddell, bears a striking resemblance to the real man, and nails Liddell’s unorthodox, slightly goofy running style. He also delivers the script with such sincerity it lands when he reads lines like, “I believe God made me for a purpose – but He also made me fast. And when I run, I feel His pleasure.” Likewise, when Liddell’s father tells him, “You can praise God by peeling a spud if you peel it to perfection. Don’t compromise. Compromise is a language of the devil. Run in God’s name, and let the world stand back and wonder,” it’s near impossible to imagine such a line in a modern mainstream movie delivered without dripping irony.

Audiences responded to the naturally compelling story. “Chariots of Fire” won four Academy Awards, including Best Picture. Its soundtrack and opening theme are nothing short of iconic, and even those who have never seen the movie will recognize the very-1980s-yet-inspiring blend of piano and synthesizer.

By today’s standards, it’s a slow movie. Then again, perhaps the carefully paced story is appropriate as it gathers momentum down the home stretch. Younger viewers may need a break or two lest they lose interest. They may be brought back in, however, by discussing the implications of the story: What would they do in Liddell’s shoes (or, more accurately, what would they do in Liddell’s track spikes)? Would they decline a chance at fame and fortune on Sunday or would they compromise? Is there anything they do that makes them “feel His pleasure”?

“Chariots of Fire” is rated PG. It contains nothing objectionable aside from drinking and smoking, from both of which Liddell notably abstains. It is available for streaming on several platforms for $2.99.

This article originally appeared in The Pathway.