Editor’s note: The following is an excerpt from “Criswell: His Life and Times” by O.S. Hawkins. The book was released this month by B&H Publishing. Reprinted by permission.

It was a cold, wind-swept winter evening in 1921, way out on the wide-open Texas plains in the little community of Texline. The old timers were fond of saying that the terrain was so flat out there that you could stand on a brick and see the Atlantic Ocean to the east and the Pacific to the west.

The little family had gathered around the dinner table for the evening meal. At one end of the table sat Wally Amos Criswell with a copy of The Searchlight alongside his plate.[i] At the other end of the table sat his wife Anna Currie Criswell, who—not to be outdone by her husband—had brought to the dinner table a copy of the Baptist Standard, the weekly Texas Baptist magazine.[ii] And between them, seated in his regular place on the side of the table, was 12-year-old W. A. Criswell. The discussion that was about to ensue was an almost nightly occurrence for the young lad as he intensely listened and watched as though he were viewing a tennis match, with volleys back and forth as his mother and his father argued over whether J. Frank Norris or George W. Truett was the greatest. Criswell would later say, “As a boy, growing up there were two tremendous heroes in our house. My father admired Frank Norris and he did it inordinately…. My father thought Frank Norris was the greatest preacher that ever lived. My mother was just the opposite. My mother thought that Frank Norris was the Devil incarnate and that all he wanted to do was tear up our Baptist convention.”[iii]

So, from his earliest recollection, W. A. Criswell was fed a steady diet of animated debate between his father, a faithful and ardent supporter and defender of Norris, and his mother, an equally convinced and passionate devotee of Truett. The evening meal took on the same climate as another meal two millennia earlier in an upper room on Mount Zion, when Jesus’s disciples argued among themselves about which of them would be the greatest in the coming kingdom. Such arguments usually end in frustration and failure. But these nightly debates around the dinner table in Texline seemed to forever sear into a young boy’s mind the attributes and attitudes, as well as the pits and pitfalls, of the two greatest pastoral titans of the first half of the twentieth century.

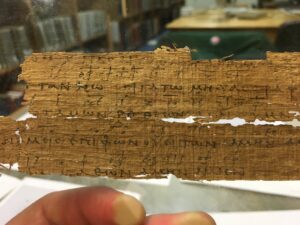

On this particular evening in Texline, the elder Criswell began to read from The Searchlight about the brewing evolution controversy at Baylor, the state’s largest Baptist college down in Waco. A prominent professor, Samuel Grove Dow, had recently published a book entitled Introduction to Sociology.[iv] Within its pages, Dow blatantly argued in favor of evolution. This sent Norris on the warpath. Father Criswell feverishly read excerpts of the book from Norris’s tabloid, stating, in Dow’s words, that prehistoric man “was a squatty, ugly, somewhat stooped, powerful being, half human and half animal, who sought refuge from the wild beast first in the trees and later in caves, and he was half way between an anthropoid ape and modern man.”[v] W. A. listened in wide eyed amusement as his father hailed the courage of Norris in exposing the blatant heretical teachings infiltrating the young Baptist minds at Baylor while excoriating Truett for his silence and perceived cover-up concerning the beloved Baptist institution.

However, at the other end of the table, Mother Criswell proved to be a formidable foe as she praised Truett for his denominational loyalty and went on the offense against Norris for his motives and methods, which, in her mind, were designed simply to create division and diversion among the Baptist faithful. Truett’s constant attempts to avoid controversy and conflict at almost any cost appealed to her inner desire to live at peace with all men. When it came to open conflict and debate, Truett, “as was his custom, remained in the background.”[vi]

W. A. Criswell went on from those dinner-table debates to become arguably one of the most influential Christian voices of the last half of the twentieth century. Later inheriting the pulpit of George Truett, Criswell built the largest church in America, numbering 25,000 members at its zenith, while maintaining his own statesman-like presence and, at the same time, incorporating the fire-brand fundamentalism and church growth principles of Frank Norris.

In a very real sense, Criswell lived his entire life with the two warring influences of Norris and Truett fighting for control within the inner recesses of his own heart and mind. He was an avowed fundamentalist when it came to theological and doctrinal matters, always elevating doctrinal loyalty above denominational loyalty. But at the same time, he fashioned himself after Truett when it came to avoiding personal conflicts and remaining above the fray as much as possible.

[i] The Searchlight was a weekly tabloid published by J. Frank Norris, pastor of the First Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas. Polemic in nature, it was the most widely read Christian weekly paper in the Southwest, with a weekly circulation of over 100,000. For a time without any modern media such as radio, television, and internet, it is difficult to convey the power of persuasion that came from the pen of Norris in those days.

[ii] The Baptist Standard,more denominationally centered, was the paper of choice of the establishment Baptists in the state of Texas. It provided news of prominent pastors and promoted the work of the ministries of Texas Baptists, especially those of its colleges and universities.

[iii] Baylor University Program for Oral History, W. A. Criswell interview by Thomas L. Carlton and Rufus B. Spain, February 3, 1972, Dallas, Texas, 20-21.

[iv] Samuel Dow, Introduction to Sociology (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, Co., 1920).

[v] Dow, Introduction to Sociology,210.

[vi] Keith Durso, Thy Will Be Done: A Biography of George W. Truett (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2009), 187.