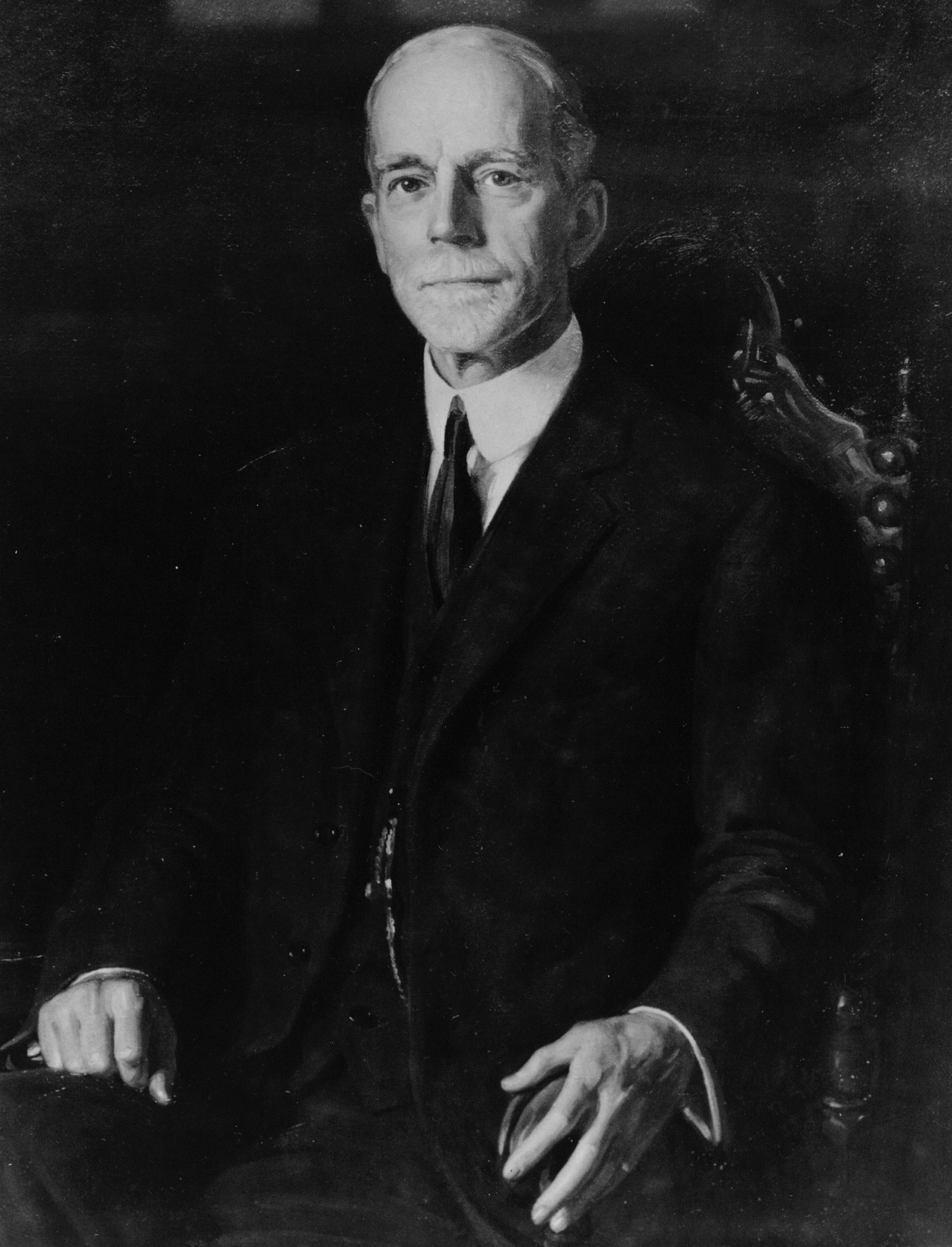

EDITORS’ NOTE: In a three-part editorial series on the Baptist Faith and Message, James A. Smith Sr., executive editor of the Florida Baptist Witness, included an essay by E.Y. Mullins titled, “Baptists and Creeds.” That essay and two editorials by Smith join Baptist Press’ publication of a series on the BF&M by faculty members of Southern Seminary in August and September. Smith notes that Mullins uses “creeds,” “confessions” and “articles of faith” interchangeably and offers a balanced defense of their use in denominational life. The most important Southern Baptist theologian of his day, Mullins was the fourth president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, serving there from 1899-1928. He was the primary architect of the first edition of the Baptist Faith and Message in 1925 and was president of the SBC from 1921-24.

LOUISVILLE, Ky. (BP)–There has been much recent discussion of Baptists and their relation to creedal statements. We usually prefer the expression “confessions of faith” because in some denominations coercion has often been associated with the creeds of the past. But properly understood a creed with Baptists means simply what we believe. Creed and confession of faith mean the same thing. I invite attention first to some fallacies about creeds.

Some Fallacies about Creeds

The first is the widely circulated statement that Baptists have no creeds. As a matter of fact, Baptists have published a large number of articles of faith. Professor McGlothin’s volume Baptist Confessions of Faith (Publication Society, 1919) has 368 pages. On these pages are printed a long list of Baptist creedal statements. These confessions were published under a great variety of circumstances. In each instance there was a good ground for the publication.

A second fallacy is that Baptist liberty prohibits creedal statements. Our traditional championship of religious liberty and individualism is constantly cited against new declarations of faith. How exactly the opposite is true. The publication of confessions of faith has been a constant expression of our ideal of liberty. Repression at this point is exactly what Baptists do not want. Repression covers up, hides beliefs, and under the cover all kinds of errors breed and flourish.

Baptists have always revolted against coercion by state or church in the matter of beliefs. This is the background of our traditional doctrine of liberty. But Baptists would sell their birthright very cheaply if, within the Baptist family itself, one group should muzzle another group to prevent a free expression of beliefs whenever the situation called for such expression. Openness and freedom of utterance are our true Baptist tradition. The coercion of a public opinion among us forbidding such free utterance would be a dire calamity — the New Testament, of course, is our final standard and authority. Our confessions are simply our effort to state what the New Testament teaches. They are all to be tested and estimated according to the New Testament.

A third fallacy is that creedal statements are government by the “dead hand.” Here again the fact has been turned right about and made to face in the wrong direction. New creedal statements are put forth to prevent government by the “dead hand.” That is why there are so many Baptist confessions of faith. No group of Baptists can bind another group by any such statement of beliefs. Creeds tend to become stereotyped in the course of time. New and vital statements are needed. To keep our faith alive we restate it from time to time.

A fourth fallacy is that creedal statements imply that we have ceased to think. This is a palpably incorrect view. We are bound to think, discriminate, construct, when we give forth new statements of belief. I make bold to say that the greater part of the thinking in theology today is being done by those who are interested in restatement of beliefs. There are two groups who are thinking hard. First, the radicals who are trying to overthrow the evangelical faith. They are framing a new scheme of doctrine. Another group who are thinking are defending the evangelical faith. There is a third group who are not thinking much — the neutrals who have no definite message and depreciate all efforts to restate the faith.

What is a Creed?

A creed is simply the statement of meaning of the facts of religion. … Confessions of faith are our efforts to state what the great facts of our religion mean.

Reasons for Opposing Restatement of Beliefs

I mention the following reasons implied or expressed, consciously or unconsciously held, for opposing new statements of belief.

I name, first, the desire for license instead of liberty. There are limits to religion of Christ beyond which men may not go and claim to be Christian, and there are corresponding Baptist limits. The refusal to define limits may and often does indicate a desire to abolish all limits.

Another reason is the absence of opinions. Real thinking is hard work. The indolent mind is impatient with strenuous doctrinal thought. It does not enjoy the attendant headache. The “open mind” is the ideal of the indolent mind. I believe in the open mind, with a screen in it, like an open window. The screen lets in the air and keeps out the mosquitoes and gnats. The screen in the mind means discrimination, and discrimination means hard thinking and definite views.

Another reason for opposing creedal statements is unwillingness to declare one’s views. Some, indeed many, who are really thinking hold views they are unwilling to declare. They have arrived at conclusions but they are held as a sort of private possession to be exposed to view only in a select inner circle. It is inevitable that these should oppose creedal statements.

A fourth reason for such opposition is an incorrect conception of liberty. This is perhaps the most widespread reason among Baptists. It is due to an exaggerated individualism. Liberty is interpreted as an individualistic affair entirely. This is erroneous. Liberty is also a social principle. It involves relations to others, obligations and duties. If you have in yourself all resources of material support, mental equipment and the inclination, you may be a free lance. But the moment you join any group other than a free lance club, you accept limitations. The Baptist denomination is not a free lance club as some would like to make it.

The group has liberties as a group. Two men or two million men have the right to unite for common ends on a common doctrinal platform, whether that platform be economic, political or religious. This is an inalienable right of the group. Free and voluntary association on a common platform for common ends is what made America an independent nation. A political party without a platform is unthinkable. A denomination controlled by a group who have no declared platform is heading for the rocks. The Baptist denomination has never allowed creeds to be imposed upon it by others. It has never compelled anyone in the denomination to accept the Baptist confessions of faith. But Baptists have always insisted upon their own right to declare their beliefs in a definite, formal way, and to protect themselves by refusing to support men in important places as teachers and preachers who do not agree with them. This group right of self-protection is a sacred as any individual right. If a group of men known as Baptists consider themselves trustees of certain great truths, they have an inalienable right to conserve and propagate those truths unmolested by others in the denomination who oppose those truths. The latter have an equal right to unite with another group agreeing with them. But they have no right to attempt to make of the Baptist denomination a free lance club.

When Are New Statements of Belief Needed?

They are needed under various circumstances. Sometimes they are needed to differentiate Baptists from other denominations, as in the Puritan era in England. Sometimes to defend themselves against false charges, as in Romania and other European countries today. Sometimes they are needed to help unify groups of Baptists scattered over the world, as was designed in the Fraternal Address of Southern Baptists two years ago. They are needed in times of doctrinal vagueness, confusion and unrest as at present.

These confessions of faith do not in any way interfere with Baptist liberty. They are never given final form. They are never free from defects. They are never imposed by legal sanctions. Their influence is moral and spiritual. No two of them are ever identical in form, although most of them agree in substance. They are never doctrinal strait-jackets like Catholic creeds. But while they do not destroy liberty they do enable Baptist life to function effectively. They educate the young believer. They enable the average church member to get his bearings. They define certain great limits within which a man is entitled to call himself a Baptist. They have the immense practical value of indicating who can work together successfully in the enterprises of the kingdom of God.

The Limits of Cooperation

The last point is worthy of emphasis. Practical cooperation is, after all, a fine test of the limits of practical fellowship, and doctrinal fellowship is a fine test of the limits of practical cooperation. The exact limits of practical cooperation are, of course, hard to define. But there are certain great guiding principles. If a man holds consistently the Unitarian view of Christ’s person, he cannot long cooperate with those who hold the deity of Christ. The two conceptions are antagonistic in themselves and in the great groups of beliefs which go with them. For the one group bad men evolve into good men in response to good influences. For the other group bad men become good men by being saved from their sins in response to the Gospel appeal. For one group education is the chief agency for changing men. For the other regeneration by the power of God’s Spirit. It is true, as often asserted, that cooperation is largely a matter of spirit and attitude. Identity of doctrinal beliefs may not be necessary at all points in order to have cooperation among groups of Baptists. But if there are radical and fundamental differences, the “spirit” and “attitude” are certain to correspond. No man can with enthusiasm give his money or his assistance in propagating what he regards as fundamental error.

Before closing I wish to add that I admit that there are dangers connected with new statements of belief. They may be misused. They may be abused in various ways. They may be put forth too frequently and absorb too much attention. But this does not affect that main point. They are a part of the vital process by which the life of a great people is expressed and promoted. As Baptists we must not permit ourselves to become silent on our fundamental beliefs in an age which calls for outspokenness in clear terms. We must not permit the formation of a public opinion among us which tends to repress and stifle.

I have written the above because there are deadly tendencies at work — deadly. I mean to our New Testament Christianity. The neutrals do not see these tendencies and make no protest. They are for peace and silence. The radicals see clearly. The defenders of the gospel also see clearly on their side. It is well that we clear the atmosphere and learn where we are drifting.

–30–

This essay, likely written between 1920 and 1925, was reprinted in 1997 as part of a compilation of Mullins’ works titled, “The Axioms of Religion” (also the title of his most famous work which is included in the volume) and published by Broadman & Holman of LifeWay Christian Resources of the Southern Baptist Convention.