Sam pointed across the road to the spot about 50 yards away where he first heard the distinctive “pop” of tear gas canisters fired at the long line of marchers descending from the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The group of 600 stretched from downtown Selma and over the Alabama River. It was the beginning of the 51-mile journey to the state capital in Montgomery to demand long-denied voting rights. Sam was 11 years old and trailing some distance behind his older brother when he saw him running from the consuming mist.

Just 200 yards ahead, at the vanguard of the peaceful march, dozens of people lay scattered in the streets in pools of their own blood, some unconscious, after law enforcement officers brutally beat them with Billy clubs. Sam could see mounted police charging his way, wildly swinging nightsticks at people in panicked retreat, landing blows to their heads and backs. Petrified, he ran after his brother, away from the horror sweeping his way.

I met Sam last week at the National Voting Rights Museum and Institute located adjacent to where the events of Selma’s Bloody Sunday (March 7, 1965) took place. He vividly remembers it all, every detail. “That was a bad day. A terrible day. I remember the looks on people’s faces as they ran in fear.”

Standing on historical ground has always been surreal to me. I try to transport my mind and imagination to the moment that made the place significant. Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church is one of those places. I stood at the east side of the church, at the point of explosion, and tried to capture the terror people must have felt. They scrambled to remove the rubble following the detonation of 19 sticks of dynamite planted by white supremacists. Four young girls were murdered and more than a dozen others seriously injured.

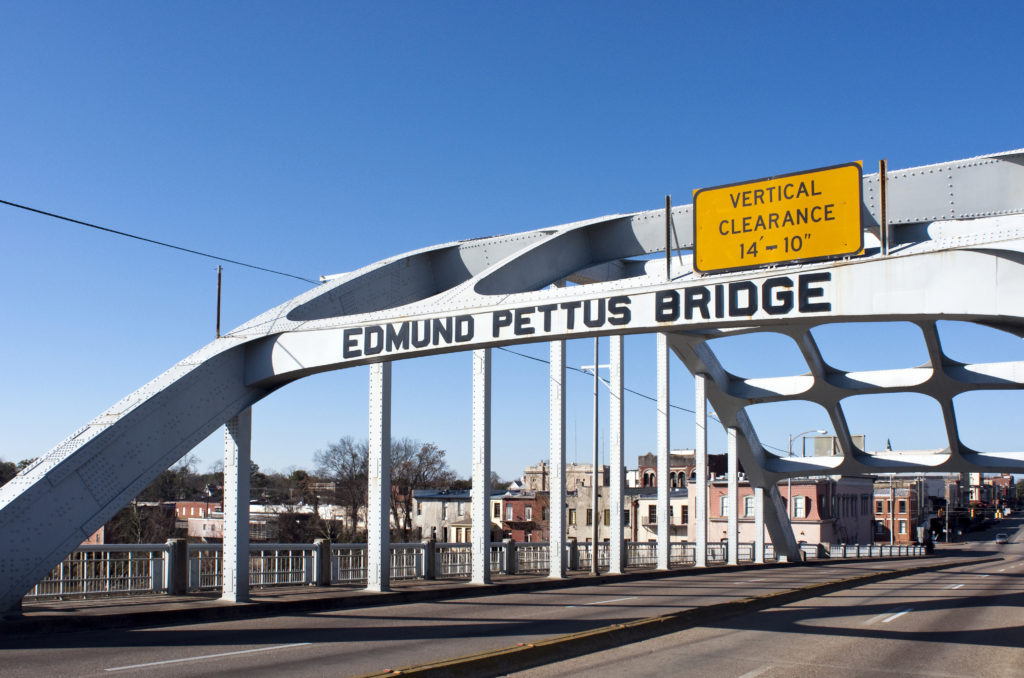

The trip to Selma and the conversation with Sam followed Birmingham. I took a solemn walk up and over the Edmund Pettus Bridge and thought about what Sam said as I wandered the streets of downtown Selma. The bridge has quite a rise and you can’t see the other side of the river until you reach its middle. On the return across the bridge, I imagined what it must have been like for marchers to crest the bridge’s apex and see a wall of law enforcement officers below dressed in full riot gear blocking the road to Montgomery.

I walked to where those officers initiated a brutal beating of defenseless people with clubs. It was nauseating. Try as I might, I simply cannot grasp how individuals could have so enthusiastically inflicted such unprovoked and unwarranted violence against their fellow man unless they rationalized the people they were beating were less than human. The sick irony is that the perpetrators were the animals, not the marchers.

Birmingham’s church and Selma’s bridge are visual reminders to me of the depravity that can so easily consume the human heart.

“There’s still so much prejudice in our world,” Sam told me. “Too much. But I’m hopeful. We gotta talk to each other though, like we are doing right now. We’re not that different, you and me. We’re both men trying to make it in this world. I just feel if we got to know each other on a personal level, things would be a lot better.”

Sam is right. As he talked, 2 Corinthians 5:14-20 came to mind. The Apostle Paul reminds us that if we are reconciled to God through Christ, we are dead to ourselves, to our old ways, to things like our prejudices. Paul tells us as ambassadors of Christ we must see and love people as Christ does, with the mission to reconcile them to God through the salvation offered by Jesus. Paul and Sam reminded me again that there is no room for prejudice in the Christian heart. Not a smidge. But Christians categorically disqualify themselves from service to Christ if their first response to anyone begins with, “Yeah, but…” The gospel is for all people and is not ours to conditionalize or withhold.

Beyond the biblical obligation that binds Christians, our society must fight the urge to cancel, change or forget history. It all matters, and every ugly detail, like the bombings, lynchings, and beatings, must be taught in balance with our greatest accomplishments. Our past must inform our future and guide us to do better for all people.

Guarantees of freedom for everyone require vigilance because freedom is fragile and as fleeting as a whisper. The prejudices harbored in our hearts for people of a different skin color must be conquered if we are to press on toward the dream of a man whose life was cut down on the balcony of a Memphis motel. However, his dream lives on and should be everyone’s dream, that “this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

Achieving the dream is possible, and it begins with a simple first step. Sam told us the way. “We gotta talk to each other.”