NASHVILLE, Tenn. (BP)–During his expedition with Jim Irwin, Ron Wyatt had been able to collect more samples than ever before. This time, the results of the analysis were nothing short of spectacular.

Wyatt believed one specimen was the remains of a metal fitting of some type. It proved to contain iron, ferric oxide, alumina and aluminum — all in concentrations too high to be natural soil. Other samples actually registered as high as 19.97 percent ferric oxide and 13.97 percent iron — 20 and 28 times the levels occurring naturally in samples Wyatt had taken outside the formation.

Irwin, the former astronaut, sent samples of the “ballast” rock to Los Alamos National Labs in New Mexico, which found manganese dioxide present at a level of 84.14 percent — far higher than the greatest natural amount previously found: 50 percent. A chemist with Reynolds Metals identified the “ballast” as waste left over from metal production, not a naturally occurring rock of any kind.

Wyatt’s confidence that they had located the remains of Noah’s Ark was growing even greater, and now he wasn’t alone. Turkish scientists examining the site had conducted their own metal detector scans and were convinced the object was a fossilized ship. In fact, Ekrem Akurgal, Turkey’s leading archeologist and a professed atheist, concluded that the formation was indeed the remains of Noah’s Ark because, he said, “there is no other explanation.”

Despite that conclusion, the Turkish government still was denying Wyatt permission to excavate the site. He couldn’t imagine how to proceed until he received a call from David Fasold, a marine salvage expert who had been directed to Wyatt by Irwin.

Fasold told Wyatt about a new, more advanced metal detector that could distinguish between different types of metal, and about a radar device that could reveal the shape of buried remains by scanning multiple times at various depths, compiling a three-dimensional picture of the object.

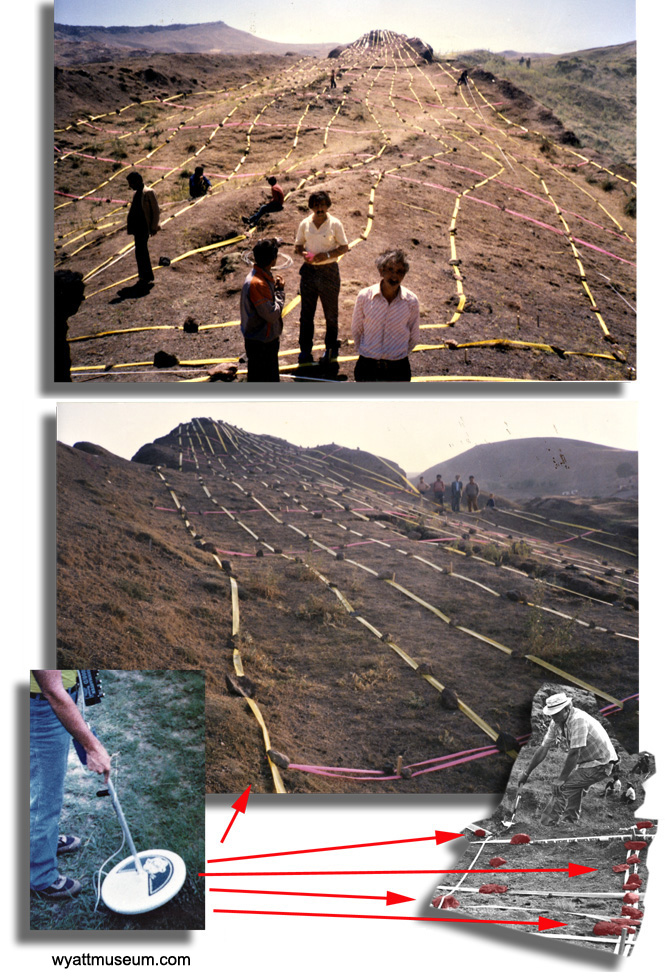

Wyatt and Fasold visited the site in June 1985 to conduct scans with the more advanced metal detectors. Each time they picked up a metal reading, they placed a rock at the spot. Then they connected the rocks with plastic tape. When they stepped back to look at the pattern, they clearly saw a ship-shaped pattern.

Wyatt knew the radar scans had to be conducted, and two months later he and Fasold proceeded to do just that.

This time, however, they were not alone. Wyatt’s impressive findings and his relationship with Irwin had gained him national attention. In August, when Ark seekers made an annual climb of Ararat’s peak, an expedition to Wyatt’s site was on the agenda. A major financier was picking up the tab, including the cost of the sophisticated radar equipment.

Even more significant, ABC’s “20/20” news magazine was covering the expedition. Wyatt felt like he finally was on the verge of laying out the evidence he believed would convince skeptical experts and academics.

It was not to be.

Kurdish separatists had become very active in the region, even attacking a team climbing Ararat. The Turkish government anticipated an attack on the high-profile expedition to Wyatt’s site.

That in fact is what happened, but when the rebels attacked, government troops sprang from hiding places and drove them off — inflicting significant rebel casualties.

The result was that martial law was declared. The site was off limits, and the expedition in which Wyatt had placed such high hopes was canceled — at great expense to all those who had spent so much money to make it possible.

NEXT: Radar scans, 1986

–30–

Based on accounts of Ron Wyatt’s expeditions archived by Wyatt Archeological Research at wyattmuseum.com.