This story has been updated since it was first posted earlier today (Feb. 4).

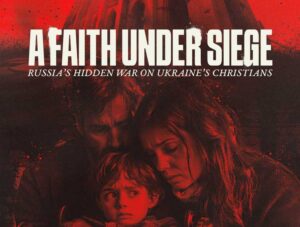

AUSTIN, Texas (BP) — In one of at least three instances of persecution of evangelical Christians in southern Mexico’s Chiapas state last month, village leaders reneged on their agreement to allow 47 evangelicals who were expelled for their faith to return to their homes and land.

In accordance with the agreement arranged by state officials, these Protestants from Buenavista Bahuitz village on Jan. 20 tried to return to their community after syncretistic Catholics expelled them in 2012 for their faith. When the Protestants and Chiapas officials accompanying them reached Buenavista Bahuitz, community leaders again refused entry until the Protestants convert to Catholicism, according to advocacy group Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW).

“Traditionalist” Catholics of the village who practice a blend of Roman Catholicism and indigenous customs involving drunken festivals have been at odds with the Protestant minority for years. Local authorities who are such syncretistic Catholics told them they could come back to their property only if they became Catholic and took part in their religious activities, including paying for the costly celebrations that involve large amounts of alcohol.

In November those expelled from Buenavista Bahuitz together with other forcibly displaced Protestants from other Chiapas communities protested their plight with a peaceful sit-in at the state government building in Tuxtla Gutierrez, the state capital. After state government officials gave the Protestants verbal commitments to address their concerns, the displaced ended their month-long action on Dec. 1.

Chiapas officials had assured the displaced group that they had negotiated their return, said Luis Herrera, director of the Coordination of Christian Organizations of Chiapas (COOC), in a CSW statement. The officials had told these evangelical Christians their freedom of religion would be protected.

But when the evangelicals and state officials arrived in the village by bus Jan. 20, Buenavista Bahuitz leaders told the former residents that they must convert to Catholicism in order to stay. When surprised state officials then intervened with the village leaders, the syncretistic Catholics at last offered to allow the evangelicals to stay if they paid a high fine.

The evangelicals declined the offer. They returned to church property in Comitán de Domínguez, where they’ve lived as displaced persons for two and half years.

The continued expulsion of the 12 families is among 30 active cases of faith-based persecution that CSW is tracking in Chiapas, an analyst from the organization told Morning Star News. The cases range from early pressure applied to villagers, such as having water or electric power cut, to local authorities denying children the right to attend school, said the analyst, who requested anonymity.

Other cases, she said, include removing Protestants from a government benefits list. Extreme cases include bans on worship, forbidding even home prayer gatherings, destruction of houses and church buildings and outright expulsions.

Exacerbating the problem is impunity in Mexico for religiously motivated crimes.

“We know of almost no cases where somebody has been prosecuted for criminal acts in the name of religion,” she said. “In Mexico, if you commit a crime, destroy your neighbor’s house, and you say it was religious, suddenly it becomes an exempt crime for some reason, [as if they] can’t touch that.”

The government also has an unhelpful practice of granting persecuted people land outside their community for resettlement; she said this is tantamount to saying to victims, “We’ll relocate you rather than deal with the root issue.”

The roots of the inaction lie in a culture holding that the majority has the “right” to decide the faith of the entire community.

“The government has allowed the persecution to develop and become entrenched,” she said. “If the government doesn’t intervene, it almost always ends with expulsion.”

Violations of religious freedom and forced displacement of religious minorities have been common for decades in Chiapas, Oaxaca, Guerrero, Hidalgo and Puebla states, where there are large indigenous populations, according to CSW. Local political bosses or caciques resort to Mexico’s “Law of Uses and Customs,” which was designed to keep the government from interfering with local indigenous customs but which syncretistic Catholics use to force evangelicals to pay for and participate in “Traditionalist” Catholic rituals.

The Law of Uses and Customs thus has been used to allow local authorities to violate, with impunity, religious rights guaranteed in the Mexican constitution, CSW noted.

“We continue to call on the state government to meet its obligations under Mexican and international law and urge the federal government to intervene if the state government is unable or unwilling to fulfill its responsibilities,” CSW Chief Executive Mervyn Thomas said in the statement.

Recent expulsions in Chiapas include that of 10 Protestants whom leaders of La Florecilla village in San Cristóbal de las Casas municipality forced to leave on Jan. 14 after the evangelical Christians refused to renounce their faith, according to CSW.

Also in Chiapas, on Jan. 8 about 25 armed, hooded individuals believed to be caciques (or local political leaders) reportedly attacked evangelicals in Las Ollas community in San Juan Chamula municipality for refusing to take part in a Virgin of Guadalupe festival in December.

Although they objected to the drunken festival on principle, the impoverished evangelicals reportedly said they were willing to pay but simply could not afford the 250 pesos (US$16) per family that village leaders demanded of them.