Render to all what is due them: tax to whom tax is due; custom to whom custom; fear to whom fear; honor to whom honor. – Romans 13:7 (NASB)

GALLATIN, Tenn. (BP)–March 25, 2003, Chief Petty Officer Jordan Joseph Garrett, United States Navy (Retired), received honors long overdue for actions that “reflected great credit” upon himself, the United States Navy and the United States of America.

When the USS Houston was attacked by Japanese ships on March 1, 1942, Garrett refused to leave the vessel until the third “abandon ship” alert was issued. With two broken feet, shrapnel in his leg and lacerated hands, Garrett managed to stay afloat in the water for an entire night after the ship sank.

As Garrett and another surviving American sailor swam in the midst of dead bodies, Japanese machine gun boats patrolled the waters, intending to kill any survivors. Garrett and the other sailor would lay still in the water, pretending to be dead in order to survive.

The two sailors eventually came upon a life raft with about 25 people on it and, the next morning, were approached by a Japanese boat. The officer in charge happened to be American-born and educated and had been drafted into the Japanese Army while visiting relatives. He told the shipwrecked Americans that he was supposed to execute them, but instead he would take them to safety. On the way to shore, they were intercepted by another Japanese boat and taken as prisoners of war.

In a ceremony held at College Heights Baptist Church in Gallatin, Tenn., 60 years after his perils began, Garrett was awarded the Purple Heart and the Prisoner of War medals for his extraordinary conduct during these events and the forty-two months of captivity that followed.

“The honor goes to the men and women on the front lines today,” Garrett said after accepting the awards and thanking his family and friends for attending the occasion.

Reflecting on the recent capture of Americans serving in Operation Iraqi Freedom, Garrett shared his thoughts on how these prisoners of war might best endure their ordeal.

“Keep the faith. Keep their heads up and rely on people back home and God to keep going,” Garrett told Baptist Press. “They’re not there because they want to be. They’re there for one purpose, to defend our nation and to liberate people who have been under bondage of a dictatorship for so long.

“You don’t go to war because you want to. Nobody wants to go to war. I don’t even believe in war, but that’s the only thing that’s going to release those people from oppression,” he said.

During his three and a half years as a prisoner of war, Garrett endured the horrors of Japanese prison camps in Java, Singapore, Burma, Thailand and French Indochina. He spent most of the last two years working on the “Death Railroad” in Burma and Thailand, including repair work on the bridge over the River Kwai. While forced to perform inhumane slave labor, Garrett was starved, beaten and tortured. He suffered from diseases such as malaria, beriberi, dysentery and tropical ulcers.

His ordeal as a prisoner of war began on a beach where the Japanese directed his boat of at least 25 American servicemen to land. In his memoirs, Garrett recalled staying on the beach for eight days, unloading Army supply cargo from huge Japanese ships. Both of his feet had been broken when the USS Houston sank and they had swollen considerably, leaving him unable to walk. Each day his buddies would carry him to the ship, he recalled, and his job was to count the supplies as they were unloaded from the ship.

After eight days, the group was transported to a movie theater in Serang, where about 500 Americans, Australians, British and Dutch prisoners of war were being held.

“That was a terrible place,” Garrett said. “There were no seats in the theater. It was so crowded, we had to take turns sleeping. Some would be sitting up while others were lying down. The only ‘sanitary facilities’ was a big ditch which we dug between the building and the wire fence outside.

“When it would rain, all the sewage would wash into the building. We stayed there for 36 days,” he said. “Each day we got one dipper of rice and about a half a cup of hot water. When I got out of that theater, I only weighed 86 pounds.”

After more agonizing experiences, in March 1943 Garrett and other prisoners of war began grueling work on the Burma/Siam Railroad, known as the Death Railroad. At the first camp, they were abused by Korean guards, who were like heathens, uncivilized and cruel, Garrett recounted.

“It was sort of the death camp where they took you to die,” he said. “They gave them almost nothing to eat. People were dying so fast that they had a hard time having enough people to bury them.”

Garrett noted that about 7,000 men died from cholera.

Soon after the railroad was finished in March 1944, Garrett and about 20 other Americans joined British POWs in repairing the bridge at the River Kwai after it was damaged by bombs. There he contracted malaria.

After marches to Malaya, Nakawn Paton, Bangkok and French Indochina, they received word that Japan had surrendered, and the American Air Force rescued them on Aug. 15, 1945.

“They took us via Rangoon to Calcutta, India, where we were placed in the hospital. Later, I was taken to Karachi, Pakistan, for several days and then finally on to the States in early October 1945,” Garrett said. “Following a brief stay in St. Albans Hospital in New York, I was given a 96-day leave and I went to Missouri, Kentucky and Arkansas to visit family.

“Following my leave, I reported to the Naval Hospital in Memphis, Tenn., in January 1946. I was married to Louise Cash on March 14, 1946, in Memphis. I reenlisted at the end of June 1946 and served until 1960.”

After retiring from the Navy, Garrett worked as a property manager for his brother-in-law, country music star Johnny Cash, and also served as a handyman for College Heights Baptist Church and Academy for 14 years.

Garrett had been raised in church and believed in God before the war, but he said he had not accepted Jesus nor given the Lord control of his life. When he was stationed in New Orleans in 1952, two preachers from his district came to his house and gave him a Bible. He watched their example for a while and decided the faith they had was genuine. One night after reading the Bible, he said he kneeled beside his bed and accepted Christ.

Since then, Garrett’s relationship with God has helped him deal with his experiences as a prisoner of war.

“It softens your heart enough that you don’t really hold it against them,” he said of his captors. “They were pretty cruel and treated me very unreasonably, but the Lord will take care of them. So I’ve just turned it over to him and let him have it.

“I meet some of the Japanese now that come here to this church occasionally from Japan, and I try to make them welcome,” he said, hoping that his gestures can help lead them to the Lord.

While Garrett spent time on the USS Houston during World War II, he observed very little Christian witness, he said, because it was too dangerous to gather in groups like Christian soldiers can today. But they had small Bibles to pass around and had ways of knowing who shared the faith.

Though he said he had not yet come to faith at the time, he was able to endure his time as a prisoner of war because he knew that most of the people he knew at home were praying for him.

“That was in my mind all the time,” he said. “My mother and my father and all of them were praying. And I now know they were because they told me so when I got home.”

–30–

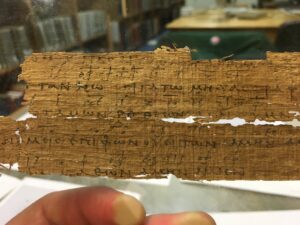

(BP) photos posted in the BP Photo Library at https://www.bpnews.net. Photo titles: WORLD WAR II PATRIOT, COLORS OF DIGNITY, PATRIOTIC MUSIC, FAMILY TIES, GIVING THANKS, HOME AGAIN and PRISONERS OF WAR.